Associated Reading 3.04

Variables and parameters are local

When you create a variable inside a function, it is local, which means that it only exists inside the function. For example:

def cat_twice(part1, part2):

cat = part1 + part2

print_twice(cat)

This function takes two arguments, concatenates them, and prints the result twice. Here is an example that uses it:

>>> line1 = 'Bing tiddle '

>>> line2 = 'tiddle bang.'

>>> cat_twice(line1, line2)

Bing tiddle tiddle bang.

Bing tiddle tiddle bang.

When cat_twice terminates, the variable cat is destroyed. If we try to print it, we get an exception:

>>> print cat

NameError: name 'cat' is not defined

Parameters are also local. For example, outside print_twice, there is no such thing as bruce.

Stack diagrams

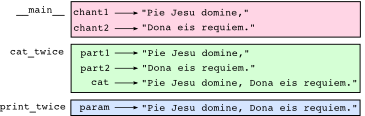

To keep track of which variables can be used where, it is sometimes useful to draw a stack diagram. Like state diagrams, stack diagrams show the value of each variable, but they also show the function to which each variable belongs.

Each function is represented by a frame. A frame is a box with the name of a function beside it and the parameters and variables of the function inside it. The stack diagram for the previous example looks like this:

Stack diagram The order of the stack shows the flow of execution. printtwice was called by cattwice, and cattwice was called by _main, which is a special name for the topmost function. When you create a variable outside of any function, it belongs to __main.

Each parameter refers to the same value as its corresponding argument. So, part1 has the same value as chant1, part2 has the same value as chant2, and param has the same value as cat.

If an error occurs during a function call, Python prints the name of the function, and the name of the function that called it, and the name of the function that called that, all the way back to the top most function.

To see how this works, create a Python script named tryme2.py that looks like this:

def print_twice(param):

print(param)

print(param)

print(cat)

def cat_twice(part1, part2):

cat = part1 + part2

print_twice(cat)

chant1 = "Pie Jesu domine, "

chant2 = "Dona eis requim."

cat_twice(chant1, chant2)

We’ve added the statement, print(cat) inside the print_twice function, but cat is not defined there. Running this script will produce an error message like this:

Traceback (innermost last):

File "tryme2.py", line 12, in <module>

cat_twice(chant1, chant2)

File "tryme2.py", line 8, in cat_twice

print_twice(cat)

File "tryme2.py", line 4, in print_twice

print(cat)

NameError: global name 'cat' is not defined

This list of functions is called a traceback. It tells you what program file the error occurred in, and what line, and what functions were executing at the time. It also shows the line of code that caused the error.

Notice the similarity between the traceback and the stack diagram. It’s not a coincidence. In fact, another common name for a traceback is a stack trace.

Aliasing

If a refers to an object and you assign b = a, then both variables refer to the same object:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = a

>>> b is a

True

The state diagram looks like:

The association of a variable with an object is called a reference. In this example, there are two references to the same object. An object with more than one reference has more than one name, so we say that the object is aliased.

If the aliased object is mutable, changes made with one alias affect the other:

>>> b[0] = 17

>>> print a

[17, 2, 3]

Although this behavior can be useful, it is error-prone. In general, it is safer to avoid aliasing when you are working with mutable objects.

List arguments

When you pass a list to a function, the function gets a reference to the list. If the function modifies a list parameter, the caller sees the change. For example, delete_head removes the first element from a list:

def delete_head(t):

del t[0]

Here’s how it is used:

>>> letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> delete_head(letters)

>>> print letters

['b', 'c']

The parameter t and the variable letters are aliases for the same object. The stack diagram looks like the following:

Since the list is shared by two frames, I drew it between them. It is important to distinguish between operations that modify lists and operations that create new lists. For example, the append method modifies a list, but the + operator creates a new list:

>>> t1 = [1, 2]

>>> t2 = t1.append(3)

>>> print t1

[1, 2, 3]

>>> print t2

None

>>> t3 = t1 + [4]

>>> print t3

[1, 2, 3, 4]

This difference is important when you write functions that are supposed to modify lists. For example, this function does not delete the head of a list:

def bad_delete_head(t):

t = t[1:] # WRONG!

The slice operator creates a new list and the assignment makes t refer to it, but none of that has any effect on the list that was passed as an argument. An alternative is to write a function that creates and returns a new list. For example, tail returns all but the first element of a list:

def tail(t):

return t[1:]

This function leaves the original list unmodified. Here’s how it is used:

>>> letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> rest = tail(letters)

>>> print rest

['b', 'c']