Associated Reading

Variables

One of the most powerful features of a programming language is the ability to manipulate variables. A variable is a name that refers to a value.

An assignment statement creates new variables and gives them values:

>>> message = 'And now for something completely different'

>>> n = 17

>>> pi = 3.1415926535897932

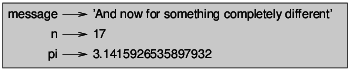

This example makes three assignments. The first assigns a string to a new variable named message; the second gives the integer 17 to n; the third assigns the (approximate) value of π to pi. A common way to represent variables on paper is to write the name with an arrow pointing to the variable’s value. This kind of figure is called a state diagram because it shows what state each of the variables is in (think of it as the variable’s state of mind). Figure 2.1 shows the result of the previous example.

The type of a variable is the type of the value it refers to.

The type of a variable is the type of the value it refers to.

>>> type(message)

<type 'str'>

>>> type(n)

<type 'int'>

>>> type(pi)

<type 'float'>

Variable names and keywords

Programmers generally choose names for their variables that are meaningful—they document what the variable is used for.

Variable names can be arbitrarily long. They can contain both letters and numbers, but they have to begin with a letter. It is legal to use uppercase letters, but it is a good idea to begin variable names with a lowercase letter (you’ll see why later).

The underscore character, _, can appear in a name. It is often used in names with multiple words, such as my_name or airspeed_of_unladen_swallow.

If you give a variable an illegal name, you get a syntax error:

>>> 76trombones = 'big parade'

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> more@ = 1000000

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> class = 'Advanced Theoretical Zymurgy'

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

76trombones is illegal because it does not begin with a letter. more@ is illegal because it contains an illegal character, @. But what’s wrong with class?

It turns out that class is one of Python’s keywords. The interpreter uses keywords to recognize the structure of the program, and they cannot be used as variable names.

Python 2 has 31 keywords:

and del from not while

as elif global or with

assert else if pass yield

break except import print

class exec in raise

continue finally is return

def for lambda try

In Python 3, exec is no longer a keyword, but nonlocal is. You might want to keep this list handy. If the interpreter complains about one of your variable names and you don’t know why, see if it is on this list.